I wake up in pain. Cramp. My leg screams. I’m in Fukushima Prefecture, Aizu-Wakamatsu, an old samurai town with a historical past. I’ve been here for a few days. I feel oddly connected to this place in a way I’m really not sure how to describe. Aizu is famous for its samurai and a red cow named Akabeko (translated to mean red cow).

I leave my hotel. The sun is so bright that the sky isn’t blue, but white, yet there are no clouds. It’s like walking through a thick fog of heat. Imagine you’re a little tiny person the size of an ant, walking through an oven set to 180 degrees. That’s what it feels like. I walk across the sheet pan in the direction of the mountains, vaguely knowing that I will arrive somewhere spirally important.

In Aizu, the legendary red Akabeko cow can be rubbed and is said to heal illness or sickness. The thing I like about Akabeko is that they have bobbing heads, so every time I walk past one I push its head down and smile as it nods up and down.

A little further up the road, Aizu-Wakamatsu is offering politeness lessons:

Don’t talk to women outside. Must bow to your elders. The two conflicting lines bother me, because as I photograph the sign, an elderly Japanese woman starts speaking to me in Japanese. Obeying the rules, I just bow my head and walk away.

A black Seven Eleven with none of the usual green and red stripes greets me funereally; I’ll soon find out why it’s black. The cascading sunshine and the black stripes make me feel as though my eyes are glitching. Outside the entrance to Sazae-do Temple, there are sweeping steps that twist all the way up, but someone has placed an escalator to one side. You have to pay 250 yen to ride it, but the cramp is threatening to return.

I don’t know what it is about today, but as soon as I step off the escalator and into an open area of monuments, the suddenness of place hits me, catching me off guard. To summarise what happened: on October 30, 1868, during the Battle of Aizu, the Byakkotai, a group of teenage samurai thought they had lost the civil war. They saw smoke in the distance, thought the castle had been sieged, so they killed themselves, not far from where I stand. Learning this, I become swallowed by sadness.

Their bodies were left outside for days, until a man, Isoji Yoshida, decided to take it upon himself to move the bodies of the dead children and bury them. For this, he was arrested. Katamori Matsudaira, the 9th lord of Aizu, wrote a poem in their honour. It goes:

“People will visit, and their tears will fall upon your graves. You will not be forgotten.”

There are monuments here for everyone involved. For the dead children, for all who died. The tomb of sixty-two fourteen- to seventeen-year-old samurai. It’s devastating. I try not to bring myself too much into these stories. But this place, these dead children, their story found its way in. I think what gets me is they don’t mention the word suicide, they explicitly state every time that they killed themselves.

I weep my way around a cemetery before turning toward the temple I originally came up this hill to see. There is a prayer wheel that, when you turn it, creates a mournful sound said to be heard in the underworld, comforting the spirits of the Byakkotai warriors. “Please turn it quietly with your heart.”

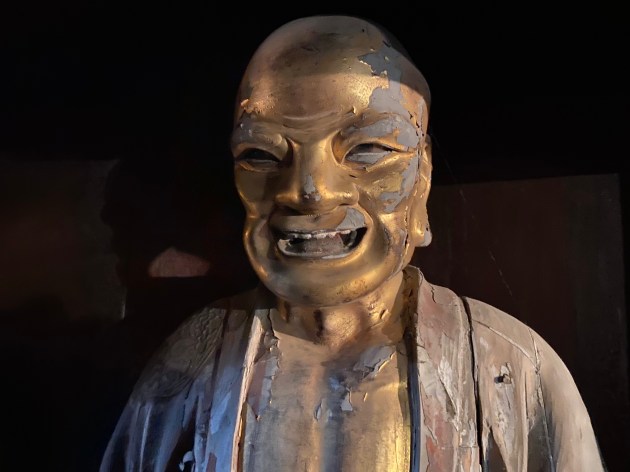

Sazae-do, a wooden Buddhist temple constructed in 1796, is famed for its distinctive spiral staircase that ascends and descends in an intricate, intertwining path. Encircling the ramp are 33 Kannon statues, each believed to grant the same spiritual merit as completing the entire Aizu Pilgrimage route to anyone who passes by them.

At 16.5 metres tall, three storeys, and shaped like a hexagon, you enter from the right side, climb the spiral staircase, and exit back down another way. You never see another soul. This valuable structure is the only wooden building of its kind from the mid-Edo period still standing in the world. It’s also the only known double-helix-shaped wooden structure in existence.

I breathe a heavy sigh before exiting through the gift shop and buying a shirt featuring Akabeko. I think about people, those loved and lost, on days when we exist together, and days when we don’t. At five o’clock, Yuyake Koyake starts playing, the song that tells the children to go back home. It elevates my sadness.

I head to a steak restaurant for dinner. I eat the red cow’s bleeding heart.

You must be logged in to post a comment.