Somewhere between October 23, 1868 and July 30, 1912, a discovery was made. What had previously been regarded as dangerous wilderness turned out to be one of the most beautiful places on Earth: Geibikei Gorge.

In Japan, they love a good top three. Night views, bridges, and today, gorges. Nobody explicitly states which of the top three is actually the best. Politeness says: make a top three list, and leave it at that. Geibikei Gorge is one of the top three gorges in Japan.

As well as being one of the top three gorges in Japan, Geibikei has also been designated a National Place of Scenic Beauty, a Natural Monument, and one of the 100 Landscapes of Japan. It certainly is one of the landscapes.

Geibikei Gorge (not to be confused with the similarly named Genbikei Gorge) is a 2-kilometre stretch surrounded by limestone cliffs. A river runs through it, so boats are required to fully explore it. The Satetsu River is a liminal, stillwater river. It flows neither up nor down. It just sits there like an ancient swamp. The only thing that interrupts the water is a boatman’s pole, or such nature as a falling leaf, the lapping of summer sweetfish, or the arrival of snakes.

We buy some fish food in a little plastic bag, then sit on the boat, all 44 of us. The boatman introduces himself.

“Hello, I am Sato. Nice to meet you.”

Everyone applauds. Sato-san notices me.

“Hey foreigner, where you from?”

I tell him England. He just laughs and begins rowing, merrily. The snake swims away, frightened by the ripples of the boat. I realise that, after all the years living in Japan, I’d never seen a snake. This is now the second day in a row I’ve seen one, and I actually manage to photograph it.

I sit, gazing out. Sato-san interrupts the serenity.

“Hey foreigner, if you have a hat, glasses, camera …” he pauses for comedic effect, then mimes dropping the items overboard. “Oh no!” he exclaims.

He then repeats the same actions in Japanese before pointing and shouting, “The next rock!” Which is of course Kyomei-Gan (Mirror Rock), reflecting the sparkle of water off its surface like a giant mirror.

There’s a phrase I can’t quite remember. Something about the memory of a fish. I remember seeing fish, so that’s probably it. They’re clever and know we have food, and they gnaw at the side of the boat, almost jumping from the water. They follow us as we disturb the stagnant river.

It’s said the sweetfish leap in early summer, and the carp in autumn. One of the carp didn’t get the memo and shows up the moment I throw my stash of food into the river. The carp makes one giant leap, eats it all, and swims away. The sight of the fish is reminiscent of the Chinese legend, known in Japan as toryumon, in which carp become dragons after successfully leaping up a waterfall.

We carry on along the river. Sato-san is very enthusiastic. He slowly pushes the boat along with the wooden pole, but does so effortlessly. We aren’t rowing. We aren’t sailing. He just pushes the pole into the riverbed, presses ever so slightly, and propels us forward. The boat drifts for a moment, carried by the newly made current, then slows to a stop. He pushes again.

He points out various rocks along the gorge, makes jokes in both Japanese and English, and treats the 44 of us as an audience in his comedy routine. His confidence shines through, lightly heckling us, answering questions, entertaining us. The entertainment is so good that I almost forget about the view.

Further in, the sun splits open the sky directly above and the heat becomes immense. Some ducks appear, looking for food, and the fish still follow. We pass a small shrine in a cave dedicated to Bishamonten, the god of treasure. Everyone stands and throws their coins across the water to the shrine. Thousands of coins surround it. More gleam beneath the surface. It must be pretty easy being the god of treasure when people just hurl money at you.

We pass a man in a watchtower holding a Nikon camera. He shouts for us to say “cheese” before taking our photo. We pass another boat heading in the opposite direction and everyone waves at everyone else, like we’re in this together. I guess we are. So we continue on. It really is indescribably beautiful.

I take a moment to think, to contemplate, to evoke. Then I take some boatographs.

Thirty minutes into the boat ride, it’s time to make land and take a break. We glide over to a pebbled beach. Sato-san says something in Japanese, then turns to me.

“Hey foreigner, twenty minutes walking come back.”

I reply that I understand, in Japanese. The other 43 people laugh.

I see somewhere on the map labelled “Ninja Rock ??” but realise, when I can’t find it, that it’s a clever joke. I pass a rock shaped like a horse’s head, and at the very end of the expanse is Senryutan (Lurking Dragon Depths). A dragon is lying in wait for its chance to rise from being a Geibi carp, apparently. If you manage to throw an undama (pebble) into the hole, you’ll be rewarded with good luck. Apparently.

I walk around for a while before boarding the boat again. Eventually, everyone returns and sits in their original seat. There’s one seat empty that wasn’t on the way down. Someone has gone missing, but Sato-san makes light of it, then pushes the boat out once more. This time, instead of taking photographs, we just take it in. And instead of narrating or pointing at rocks, Sato-san begins to sing.

“Song time,” he says. “Very old time song. I do five or six minutes… maybe.”

He sings for twenty.

His voice transforms into something ancient, filling the gorge, lingering among the cliffs:

As I pole my boat,

on the clear waters of the Satetsu River,

the clouds,

that dull my heavy heart,

are dispelled,

by the Lion’s Snout.

His voice echoes long after the last note fades.

After singing, he looks exhausted, yet continues to carry us through the gorge in reflective silence. Nobody speaks. Even the water has quietened. I’m glad that of the multiple boatmen working today, that we were lucky enough to have Sato-san as our guide. His personality and comedic timing were a highlight, one of the most memorable experiences I’ve had in Japan.

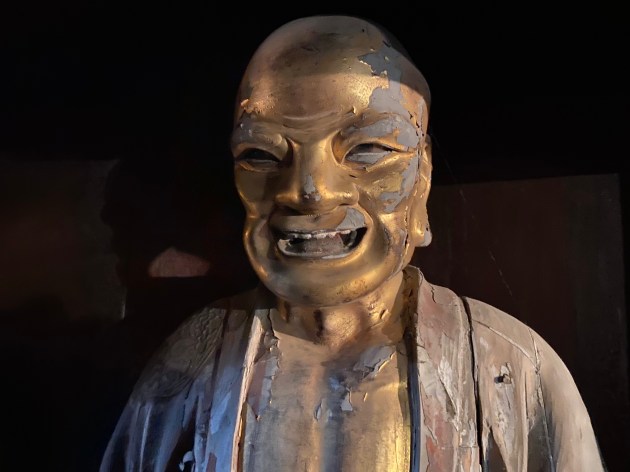

After the boat ride ends, we drift back into the real world. The gift shop waits patiently. A vending machine hums to the tune of overpriced green tea. I leave and take a train back to Morioka, walking the quiet streets until I reach Hoonji Temple. I take off my shoes and enter the silence. Inside the main hall, 499 rakan statues sit frozen in time.

They were hand-carved three centuries ago by nine monks. Each statue is lacquered, lifelike, and unmistakably human. Some laugh. Some grimace. A few seem lost in conversation. It’s almost as though I can hear them talking to one another. One of them is definitely Tom Waits. Others are said to resemble Marco Polo or Genghis Khan. There’s an expression to match everyone.

My eyes, for whatever reason, are drawn to a rakan sitting quietly in the corner, with a face I know well. It’s not me. It’s Sato-san. The boatman. Same smile. Same humour behind the eyes.

I blink, but he’s still there.

I never did find the one that looked like me.

Maybe I’m still being carved.

![viewfromryokan[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/viewfromryokan1.jpg?w=630)

![hotwaterlake[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/hotwaterlake11.jpg?w=630)

![redleaves[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/redleaves1.jpg?w=630)

![nikkonature[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nikkonature1.jpg?w=630)

![nikkopag[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nikkopag1.jpg?w=630)

![nicesmoking[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nicesmoking1.jpg?w=630)

![nikkostation[1]](https://japanising.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nikkostation1.jpg?w=630)

You must be logged in to post a comment.