There’s a massive clock outside Kii-Katsuura Station. Each tick sounds like a nail being hammered into a coffin. About a twenty-minute walk from the station, between the mountains and sea of Wakayama Prefecture sits Fudarakusan-ji, a small, unassuming Buddhist temple with a wooden boat outside.

The temple was built to face the Pacific Ocean because that is the perfect location for casting boats out to sea. The only problem with these boats was the reason they were cast out; the priests inside them were trying to reach Fudaraku, the Pure Land.

The boats were designed with a sealed cabin, no windows or doors; a claustrophobics nightmare. Ever had a dream about being buried alive? The priests here lived it. They’d climb inside, and the boats would be nailed shut from the outside. The orange wood and torii gates surrounding all four sides of the boat are a nice touch.

Water, a small supply of food, and a fuel lamp were placed inside before the priest’s departure. The lamp was there so the priest could keep reciting sutras and appeals to Kannon until they found the Pure Land, until they reached the end of their journey, or their life.

Some of the boats washed up in Kii-Katsuura Bay. A few priests escaped. Most died of starvation, drowning, or dehydration. To stay on theme, I book a night in Urashima. To get there, I have to board a boat myself. This one features no death, just a turtle mascot. The four huge buildings making up the backdrop are all part of my hotel: one on top of a mountain with an observation platform, one at the side of the mountain connected through a network of tunnels, one at the base of the mountain by the dock, and one that isn’t shown on any maps but is there, accessed through the labyrinth.

Checking into my accommodation I’m provided a map. The hotel is so large it features a multitude of interconnected buildings attached through tunnels and cave systems carved into a mountain. The place describes itself as a resort and spa. It has everything: five onsen baths, a games centre, karaoke rooms, a Lawson Stores, shopping streets, massage parlours, restaurants for eating, ballrooms for dancing, ball rooms for ball games, conference rooms, well you get the idea.

There’s one area where I have to take multiple escalators rising the length of 154 metres that take about five minutes. There’s rest areas between each escalator with sofas and tables, just in case the standing becomes too much. I exit onto the 32nd floor and admire the view.

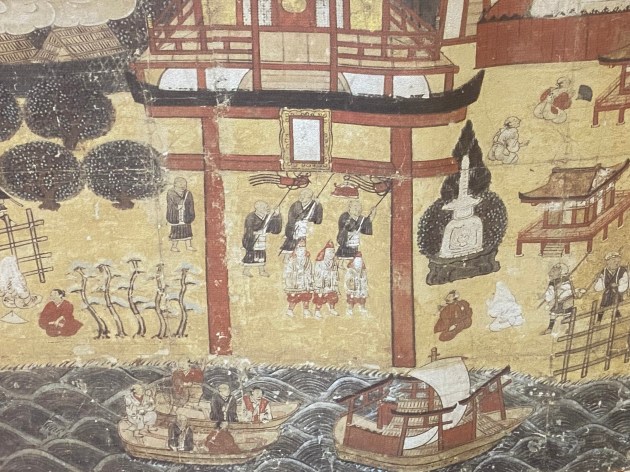

On one of the random floors, I find a replica of an original painted tapestry held in the Treasure Hall at Kumano-Nachi Taisha Grand Shrine. I’ll visit there tomorrow, weather permitting. The full tapestry features the Nachi Pilgrimage Mandala, which displays all the details of this area, from the top of the waterfalls down to Fudarakusan-ji. Here, at the bottom, one of the boats is being cast away into the Pacific Ocean.

Walking through the hotel, I feel as though I’m in some cult dystopian movie. Everyone is walking around in matching yukata. Some of the tourists are not Japanese and wear their yukata crossed the wrong way, for funerals. Everyone goes for breakfast at the same time, for dinner at the same time.

The hotel feels almost haunted, some entire areas are abandoned. It would be the perfect setting for a horror movie. It makes me feel like a rat in a maze or a character in Severance as I navigate the hotel’s endless, echoing corridors.

Having just about explored every length of the hotel, I decide to end the day by soaking in the healing power of a hot spring bath. Of the five to choose from, I opt for the one carved into a cave that looks out onto the Pacific Ocean.

The onsen is so peaceful that I no longer feel as though I’m in a hotel. Sadly, I’m not allowed to take photographs in the onsen, for obvious reasons, so instead, here is the view from the 32nd floor looking out into the bay, the 40 degree sky, and the town of Nachi-Katsuura.

I sit, submerged in hot water, staring past the cave and out to sea. I think of the lost souls who once set off from this shore, sealed inside a boat, nailed shut.

You must be logged in to post a comment.