Today, I’m in Yoro, a town in Gifu Prefecture.

I’m here to change my destiny.

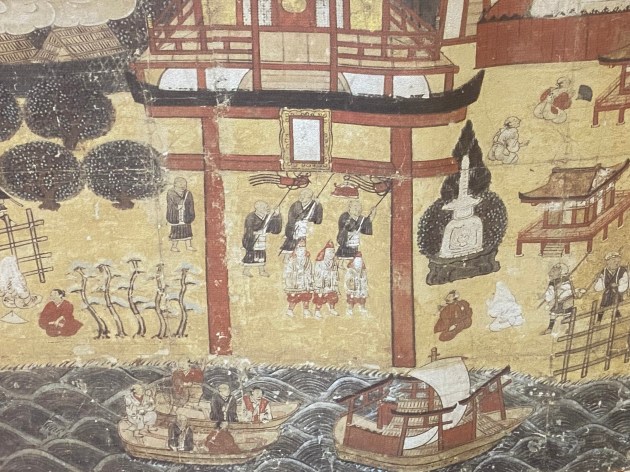

First, I decide to take a thirty-minute stroll along the edge of a cliff to visit a famous waterfall. This waterfall is said to be made entirely of flowing alcohol, specifically Japanese sake.

The story goes that there was once a poor lumberjack with a very old, ill father. On his deathbed, the father requested his favourite Japanese sake, but the lumberjack couldn’t afford it on his meagre income. One day, the son walked the treacherous path near the waterfall.

Some say he was out looking for wood for a fire, but he was a woodcutter, so any tree would have sufficed. Others say he was simply thirsty. Regardless, he fell in the woods and definitely made a sound, and after falling and lying on the dirty ground, the poor lumberjack could smell the sweet scent of sake.

It was here that he discovered the water from the waterfall was not water at all.

He returned home with a gourd full of sake, and his father drank it. The transformation was instant, and he miraculously became younger and healthier.

News of this reached the ancient capital of Nara, and Empress Gensho visited the waterfall herself. She was so impressed by the beauty of the area and the magical water that she declared it a sacred site and renamed the area Yoro, meaning elderly care.

It takes me about an hour to reach the waterfall despite it being advertised as a thirty-minute stroll. It’s a tough hike too, up a mountain. It’s humid; it feels like 40 degrees. I’ve probably sweated more water than I’ve seen flow down the falls. I can only imagine how hard it must have been for the lumberjack, carrying that gourd and heavy axe to the top.

Next to the waterfall, a faded poem engraved on stone in Japanese reads:

“Listening to the flow of Yoro Falls,

One’s heart is healed and refreshed,

Like the pure sake that rejuvenated the old man,

Flowing eternally, blessing those who visit.”

I stand looking at the waterfall for a time, enveloped in tranquillity. I think about water flowing down a river, following a predestined path. It cascades over the falls, flows further south, and meets a tributary, where its path diverges and its destination shifts, a choice not made but followed.

Somewhere, after leaving Yoro Falls, a butterfly shivers against the wind. At the bottom of the waterfall, the tranquillity ends and is swamped by the sound of a man with a grass strimmer.

I stumble upon a small souvenir shop selling bottles of carbonated cider made with the magical sake water. The cider tastes delicious. Unlike in England, cider in Japan is a soft drink, so despite the falls apparently being made of alcohol, this drink somehow contains none.

I leave with a healed heart, feeling blessed. Eternally refreshed. Next to the small shop is the Yoro Gourd Museum. I look at a few gourds made into artwork and lamps before moving on.

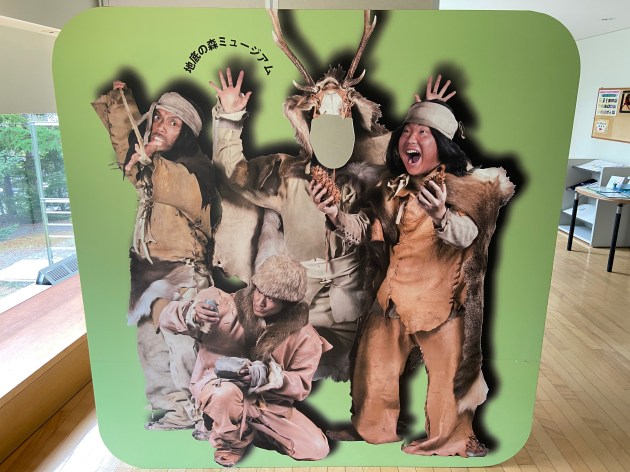

My final stop today is within Yoro Park, a place known as the Site of Reversible Destiny. A massive outdoor interactive art park dreamed up by Shusaku Arakawa.

It’s quite bizarre, funny, and downright unusual. There’s a house that is a road and a road that is a house. There’s a nostalgia generator, a few mazes, and some piles of things that I don’t even understand.

I pass Not To Disappear Street, the Gate of Non-Dying, and an area known as Geographic Ghost. I climb over the Zone of Clearest Confusion, leave through the Trajectory Membrane Gate, before getting lost in the multicolour of Destiny House.

Shusaku Arakawa was obsessed with the idea of death and destiny. He built this site with his wife, Madeline Gins, as a challenge to mortality itself. That’s the point of the Site of Reversible Destiny: to confuse your soul and reroute your path. When Arakawa died in 2010, his wife said, “This mortality thing is bad news.”

With fate as mutable as the weather, or the seeds of a dandelion, you blow away, only to take root in unexpected soil. My destiny begins to unravel. The sun still rises in the morning and sets in the west, but the days no longer feel the same. Each moment becomes a whispered echo of a choice that altered everything, carried on a timeless breeze.

The concept of a multiverse unfolds like a kaleidoscope of infinite reflections, where certainty and uncertainty intertwine like vines in an ancient forest, tangling into something that resembles fate.

Yet, if every possible outcome and path exists, there must also be a universe where the notion of such multiverses is impossible. It is here that we find ourselves staring into the paradoxical abyss.

Sweeping aside the contradiction of parallel worlds, it is on the train that I ponder the existence of a universe where I do not exist. As the train changes track to a branching line, the landscape blurs past, indifferent to my absence. My reflection in the window shimmers, quantum-thin.

For a moment, I am here and not here, observed and unobserved, a wave function waiting to collapse. I step off the train. I step into the world. And the world, impossibly, steps into me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.