The news tells me that today there is an excessive heat warning in place in Wakayama. My oh-so-reliable weather application tells me that it will be cloudy all day. The gods split the difference. As I exit the bus unprepared for anything other than heat or cloud, the heavens split open in a thunderous rage of fury.

I am at Kumano-Nachi Taisha. As the thunder rolls over the sky I manage to take just one photograph of a torii gate and the mountains beyond, right then, before the rain catches up with the thunder. Luckily for me, there is a shop, so I enter, purchase, then poncho up.

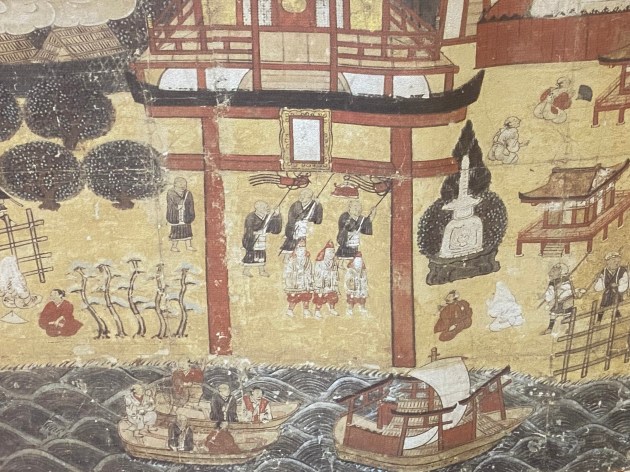

I duck inside the Treasure Hall. No photos allowed, but I explore freely. I wrote about the Nachi Pilgrimage Mandala yesterday, but seeing the real thing up close is something else. I enjoy the other art, artefacts, simple objects from a time lost in the past. Most of the treasures here were discovered in 1918, but are from around the 10th century, with the shrine itself being 1,700 years old.

Stepping out of the Treasure Hall, the rain has intensified fivefold, and some of the ground has already flooded. People cower with umbrellas.

The rainwater crashes down and smashes into the roof of the shrine like a torrent of broken glass, slicing through the air with a merciless, unyielding force. I have never experienced rain like it. The raindrops actually hurt.

I came for the waterfall. Or so I believed. Right now, I feel like I’m inside one. I struggle to see where the waterfall could even be in comparison to the falling water. A monk passes me, dressed in dark blue. He carries an umbrella and seamlessly manoeuvres the flooding and the puddles, calm as you like.

Legend has it that the first emperor of Japan, Emperor Jinmu, found the waterfalls when his boat landed on the Kii Peninsula and he saw something shining in the mountains. At the time, he had been following a Yatagarasu (a mythical three-legged crow sent by the gods as a guide).

I follow the path down the mountain toward Nachi Falls. The sky bellows with more thunder, the road is full of water. Am I walking in the rain? Or am I swimming in a river? At points the water is knee-high. The drains can’t handle it. I can barely handle it, but I persevere.

I make it to the pagoda view, the one that’s often featured on the cover of a largely poorly written guidebook. They’ve never featured it in the rain. I enjoy my photograph very much.

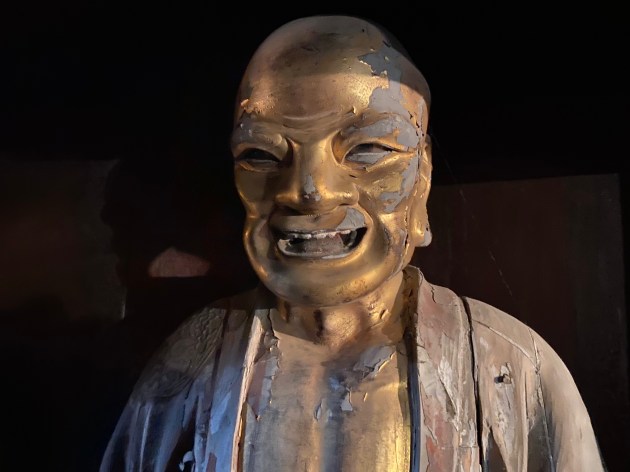

Beside the pagoda sits a big statue of Hotei. God of fortune. The Laughing Buddha. Naturally, despite my soaking wet legs and shoes and inability to understand the point of it all, I rub his massive belly. Good luck and prosperity coming my way, again.

I venture on, down flooded sloped paths and dangerous steps, and eventually, I do arrive at Nachi Falls. The heavier rain drowns out the sound of the waterfall. There’s a story of some star-crossed lovers that leapt from the top of the waterfall in the belief that they would be reborn into Kannon’s paradise. I also know that this is one of the Top Three Waterfalls in Japan, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and also plummets 133 metres, making it the tallest in Japan.

I head down some slippery steps, careful to hold the handrail. Below, the waterfall itself. Having already taken a spectacular photograph of the rain-soaked pagoda pavilion with Nachi Falls as a backdrop, I find it to be immensely difficult to capture the waterfall from up close, due to the intense rain and heavy flooding.

I stumble back up stone steps to a bus stop. Typically, upon arriving back at Kii-Katsuura Station, the rain suddenly stops. At the Turtle Boat back to my hotel, I stand at the dock. A Japanese salaryman stands beside me, perfectly dry. He glances at my poncho and then at the sky.

From the boat, I see a crow in the air. It looks as though it has three legs, but it’s just the tail feathers, fanned out in silhouette against the sky. Something that could easily be mistaken for three legs.

Back at the hotel, I hairdryer my shoes for two hours whilst waiting for my laundry to wash and dry, before heading out in search of a crow to photograph. In the end, all I find is this lousy t-shirt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.